what did Marco Polo say in his writings that led some to disbelieve his stories

A page of The Travels of Marco Polo | |

| Authors | Rustichello da Pisa and Marco Polo |

|---|---|

| Original title | Livres des Merveilles du Monde |

| Translator | John Frampton |

| Land | Commonwealth of Venice |

| Language | Franco-Venetian |

| Genre | Travel literature |

| Publication date | c. 1300 |

| Dewey Decimal | 915.042 |

Volume of the Marvels of the World (Italian: Il Milione , lit. 'The Million', deriving from Polo's nickname "Emilione"),[1] in English commonly called The Travels of Marco Polo , is a 13th-century travelogue written downwards past Rustichello da Pisa from stories told by Italian explorer Marco Polo, describing Polo's travels through Asia between 1271 and 1295, and his experiences at the court of Kublai Khan.[two] [3]

The book was written by romance author Rustichello da Pisa, who worked from accounts which he had heard from Marco Polo when they were imprisoned together in Genoa.[four] Rustichello wrote it in Franco-Venetian,[5] [6] [seven] a cultural language widespread in northern Italy between the subalpine chugalug and the lower Po between the 13th and 15th centuries.[8] It was originally known equally Livre des Merveilles du Monde or Devisement du Monde (" Description of the Globe "). The book was translated into many European languages in Marco Polo's own lifetime, but the original manuscripts are now lost, and their reconstruction is a matter of textual criticism. A full of about 150 copies in diverse languages are known to be, including in French,[9] Tuscan, two versions in Venetian, and 2 different versions in Latin.

From the beginning, in that location has been incredulity over Polo'due south sometimes fabulous stories, too as a scholarly debate in recent times.[10] Some have questioned whether Marco had really travelled to Communist china or was just repeating stories that he had heard from other travellers.[eleven] Economic historian Marking Elvin concludes that recent work "demonstrates by specific example the ultimately overwhelming probability of the wide authenticity" of Polo's account, and that the book is, "in essence, authentic, and, when used with intendance, in broad terms to be trusted as a serious though obviously non always terminal, witness."[12]

History [edit]

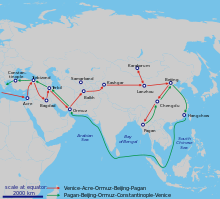

The road Polo describes.

The probable view of Marco Polo's ain geography (drawn past Henry Yule, 1871).

The source of the title Il Milione is debated. One view is it comes from the Polo family's use of the proper noun Emilione to distinguish themselves from the numerous other Venetian families bearing the name Polo.[13] A more common view is that the proper noun refers to medieval reception of the travelog, namely that it was total of "a million" lies.[14]

Modern assessments of the text usually consider it to be the record of an observant rather than imaginative or analytical traveller. Marco Polo emerges as existence curious and tolerant, and devoted to Kublai Khan and the dynasty that he served for 2 decades. The book is Polo'south account of his travels to China, which he calls Prc (north China) and Manji (south China). The Polo party left Venice in 1271. The journey took three years after which they arrived in Cathay as information technology was and so called and met the grandson of Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan. They left China in late 1290 or early 1291[15] and were back in Venice in 1295. The tradition is that Polo dictated the book to a romance author, Rustichello da Pisa, while in prison in Genoa betwixt 1298–1299. Rustichello may have worked up his first Franco-Italian version from Marco'southward notes. The volume was then named Devisement du Monde and Livres des Merveilles du Monde in French, and De Mirabilibus Mundi in Latin.[16]

Role of Rustichello [edit]

The British scholar Ronald Latham has pointed out that The Book of Marvels was in fact a collaboration written in 1298–1299 between Polo and a professional author of romances, Rustichello of Pisa.[17] It is believed that Polo related his memoirs orally to Rustichello da Pisa while both were prisoners of the Genova Republic. Rustichello wrote Devisement du Monde in Franco-Venetian linguistic communication.[18]

Latham likewise argued that Rustichello may accept glamorised Polo'southward accounts, and added fantastic and romantic elements that made the book a bestseller.[17] The Italian scholar Luigi Foscolo Benedetto had previously demonstrated that the book was written in the same "leisurely, conversational style" that characterised Rustichello's other works, and that some passages in the book were taken verbatim or with minimal modifications from other writings by Rustichello. For example, the opening introduction in The Book of Marvels to "emperors and kings, dukes and marquises" was lifted straight out of an Arthurian romance Rustichello had written several years earlier, and the business relationship of the second meeting between Polo and Kublai Khan at the latter's courtroom is well-nigh the same as that of the arrival of Tristan at the courtroom of King Arthur at Camelot in that same book.[nineteen] Latham believed that many elements of the book, such as legends of the Centre East and mentions of exotic marvels, may take been the piece of work of Rustichello who was giving what medieval European readers expected to find in a travel volume.[xx]

Role of the Dominican Lodge [edit]

Apparently, from the very beginning Marco'south story angry contrasting reactions, as it was received by some with a sure disbelief. The Dominican father Francesco Pipino was the author of a translation into Latin, Iter Marci Pauli Veneti in 1302, only a few years after Marco's return to Venice. Francesco Pipino solemnly affirmed the truthfulness of the book and defined Marco as a "prudent, honoured and faithful man".[21] In his writings, the Dominican brother Jacopo d'Acqui explains why his contemporaries were skeptical virtually the content of the book. He also relates that before dying, Marco Polo insisted that "he had told only a half of the things he had seen".[21]

Co-ordinate to some recent research of the Italian scholar Antonio Montefusco, the very close relationship that Marco Polo cultivated with members of the Dominican Club in Venice suggests that local fathers collaborated with him for a Latin version of the volume, which ways that Rustichello'due south text was translated into Latin for a precise will of the Order.[22]

Since Dominican fathers had among their missions that of evangelizing foreign peoples (cf. the role of Dominican missionaries in China[23] and in the Indies[24]), it is reasonable to think that they considered Marco's book as a trustworthy piece of information for missions in the East. The diplomatic communications between Pope Innocent Four and Pope Gregory X with the Mongols[25] were probably another reason for this endorsement. At the time, there was open discussion of a possible Christian-Mongul alliance with an anti-Islamic function.[26] In fact, a mongol delegate was solemnly baptised at the Second Council of Lyon. At the Council, Pope Gregory Ten promulgated a new Crusade to start in 1278 in liaison with the Mongols.[27]

Contents [edit]

The Travels is divided into 4 books. Volume One describes the lands of the Eye E and Cardinal Asia that Marco encountered on his style to Cathay. Book Two describes China and the court of Kublai Khan. Book Three describes some of the coastal regions of the East: Japan, India, Sri Lanka, S-E Asia, and the east coast of Africa. Book 4 describes some of the and so-contempo wars amid the Mongols and some of the regions of the far n, like Russian federation. Polo's writings included descriptions of cannibals and spice-growers.

Legacy [edit]

The Travels was a rare pop success in an era before press.

The impact of Polo's volume on cartography was delayed: the first map in which some names mentioned by Polo announced was in the Catalan Atlas of Charles V (1375), which included 30 names in People's republic of china and a number of other Asian toponyms.[28] In the mid-fifteenth century the cartographer of Murano, Fra Mauro, meticulously included all of Polo's toponyms in his 1450 map of the world.

A heavily annotated copy of Polo's book was amid the holding of Columbus.[29]

Subsequent versions [edit]

French "Livre des merveilles" front page[30]

Handwritten notes by Christopher Columbus on the Latin edition of Marco Polo'due south Le livre des merveilles.

Marco Polo was accompanied on his trips by his father and uncle (both of whom had been to Red china previously), though neither of them published any known works well-nigh their journeys. The volume was translated into many European languages in Marco Polo'southward own lifetime, merely the original manuscripts are now lost. A full of nearly 150 copies in diverse languages are known to exist. During copying and translating many errors were fabricated, so there are many differences betwixt the various copies.[31]

According to the French philologist Philippe Ménard,[32] there are six main versions of the volume: the version closest to the original, in Franco-Venetian; a version in Old French; a version in Tuscan; 2 versions in Venetian; 2 unlike versions in Latin.

Version in Franco-Venetian [edit]

The oldest surviving Polo manuscript is in Franco-Venetian, which was a diverseness of Quondam French heavily flavoured with Venetian dialect, spread in Northern Italy in the 13th century;[6] [7] [33] for Luigi Foscolo Benedetto, this "F" text is the basic original text, which he corrected by comparing it with the somewhat more than detailed Italian of Ramusio, together with a Latin manuscript in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana.

Version in Erstwhile French [edit]

A version written in Old French, titled Le Livre des merveilles (The Volume of Marvels).

- This version counts 18 manuscripts, whose most famous is the Code Fr. 2810.[34] Famous for its miniatures, the Code 2810 is in the French National Library. Another Quondam French Polo manuscript, dating to around 1350, is held by the National Library of Sweden.[35] A disquisitional edition of this version was edited in the 2000s by Philippe Ménard.[32]

Version in Tuscan [edit]

A version in Tuscan (Italian language) titled Navigazione di messer Marco Polo was written in Florence by Michele Ormanni. It is found in the Italian National Library in Florence. Other early on important sources are the manuscript "R" (Ramusio'southward Italian translation offset printed in 1559).

Version in Venetian [edit]

The version in Venetian dialect is total of mistakes and is not considered trustworthy.[32]

Versions in Latin [edit]

- 1 of the early manuscripts, Iter Marci Pauli Veneti , was a translation into Latin made past the Dominican blood brother Francesco Pipino in 1302,[36] only three years afterwards Marco'due south return to Venice. This testifies the deep interest the Dominican Society had in the book. Co-ordinate to recent enquiry by the Italian scholar Antonio Montefusco, the very shut relationship Marco Polo cultivated with members of the Dominican Club in Venice suggests that Rustichello's text was translated into Latin for a precise will of the Order,[22] which had among its missions that of evangelizing foreign peoples (cf. the role of Dominican missionaries in People's republic of china[23] and in the Indies[37]). This Latin version is conserved by 70 manuscripts.[32]

- Another Latin version called "Z" is conserved but by one manuscript, which is to exist found in Toledo, Kingdom of spain. This version contains about 300 small curious boosted facts virtually religion and ethnography in the Far Due east. Experts wondered whether these additions were from Marco Polo himself.[32]

Critical editions [edit]

The outset try to collate manuscripts and provide a disquisitional edition was in a volume of collected travel narratives printed at Venice in 1559.[38]

The editor, Giovan Battista Ramusio, collated manuscripts from the offset office of the fourteenth century,[39] which he considered to exist " perfettamente corretto " ("perfectly correct"). The edition of Benedetto, Marco Polo, Il Milione , under the patronage of the Comitato Geografico Nazionale Italiano (Florence: Olschki, 1928), collated sixty boosted manuscript sources, in improver to some eighty that had been collected by Henry Yule, for his 1871 edition. It was Benedetto who identified Rustichello da Pisa,[40] equally the original compiler or agent, and his established text has provided the ground for many modern translations: his own in Italian (1932), and Aldo Ricci's The Travels of Marco Polo (London, 1931).

The first English translation is the Elizabethan version past John Frampton published in 1579, The most noble and famous travels of Marco Polo, based on Santaella's Castilian translation of 1503 (the start version in that language).[41]

A. C. Moule and Paul Pelliot published a translation nether the title Clarification of the Earth that uses manuscript F as its base and attempts to combine the several versions of the text into one continuous narrative while at the same fourth dimension indicating the source for each section (London, 1938). ISBN 4871873080

An introduction to Marco Polo is Leonard Olschki, Marco Polo'southward Asia: An Introduction to His "Description of the Earth" Chosen "Il Milione", translated by John A. Scott (Berkeley: University of California) 1960; it had its origins in the celebrations of the vii hundredth anniversary of Marco Polo'south birth.

Authenticity and veracity [edit]

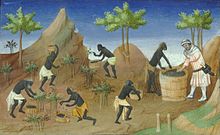

Le livre des merveilles, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, fr. 2810, Tav. 84r "Qui hae sì gran caldo che a pena vi si puote sofferire (...). Questa gente sono tutti neri, maschi e femmine, due east vanno tutti ignudi, se non se tanto ch'egliono ricuoprono loro natura con un panno molto bianco. Costoro non hanno per peccato veruna lussuria"[42]

Since its publication, many accept viewed the book with skepticism. Some in the Heart Ages viewed the book simply every bit a romance or fable, largely because of the sharp deviation of its descriptions of a sophisticated civilisation in China to other early accounts past Giovanni da Pian del Carpine and William of Rubruck who portrayed the Mongols as "barbarians" who appeared to belong to "another globe".[43] Doubts accept also been raised in later centuries about Marco Polo's narrative of his travels in Prc, for instance for his failure to mention a number of things and practices ordinarily associated with China, such as the Chinese characters, tea, chopsticks, and footbinding.[44] In item, his failure to mention the Dandy Wall of China had been noted as early as the centre of the seventeenth century.[45] In add-on, the difficulties in identifying many of the identify names he used also raised suspicion virtually Polo'southward accounts.[45] Many have questioned whether or not he had visited the places he mentioned in his itinerary, or he had appropriated the accounts of his father and uncle or other travelers, or doubted that he even reached China and that, if he did, perchance never went beyond Khanbaliq (Beijing).[45] [46]

Historian Stephen Grand. Haw however argued that many of the "omissions" could exist explained. For example, none of the other Western travelers to Yuan dynasty China at that fourth dimension, such every bit Giovanni de' Marignolli and Odoric of Pordenone, mentioned the Great Wall, and that while remnants of the Wall would have existed at that time, information technology would not take been significant or noteworthy every bit it had non been maintained for a long time. The Great Walls were built to keep out northern invaders, whereas the ruling dynasty during Marco Polo's visit were those very northern invaders. The Mongol rulers whom Polo served besides controlled territories both northward and south of today'south wall, and would have no reasons to maintain any fortifications that may accept remained there from the earlier dynasties. He noted the Slap-up Wall familiar to us today is a Ming structure built some two centuries subsequently Marco Polo's travels.[47] The Muslim traveler Ibn Battuta did mention the Nifty Wall, just when he asked about the wall while in China during the Yuan dynasty, he could find no one who had either seen it or knew of anyone who had seen it.[47] Haw also argued that practices such as footbinding were not common even among Chinese during Polo's time and almost unknown amongst the Mongols. While the Italian missionary Odoric of Pordenone who visited Yuan China mentioned footbinding (information technology is withal unclear whether he was just relaying something he heard as his description is inaccurate),[48] no other foreign visitors to Yuan People's republic of china mentioned the practice, perhaps an indication that the footbinding was non widespread or was not adept in an extreme form at that time.[49] Marco Polo himself noted (in the Toledo manuscript) the dainty walk of Chinese women who took very brusque steps.[47]

It has as well been pointed out that Polo'southward accounts are more than accurate and detailed than other accounts of the periods. Polo had at times denied the "marvelous" fables and legends given in other European accounts, and as well omitted descriptions of strange races of people then believed to inhabit eastern asia and given in such accounts. For example, Odoric of Pordenone said that the Yangtze river flows through the land of pygmies only three spans high and gave other fanciful tales, while Giovanni da Pian del Carpine spoke of "wild men, who do not speak at all and have no joints in their legs", monsters who looked like women but whose menfolk were dogs, and other as fantastic accounts. Despite a few exaggerations and errors, Polo'due south accounts are relatively costless of the descriptions of irrational marvels, and in many cases where nowadays (by and large given in the first office before he reached Cathay), he made a clear distinction that they are what he had heard rather than what he had seen. It is also largely free of the gross errors in other accounts such equally those given past the Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta who had confused the Yellow River with the M Canal and other waterways, and believed that porcelain was made from coal.[50]

Many of the details in Polo'south accounts have been verified. For case, when visiting Zhenjiang in Jiangsu, Cathay, Marco Polo noted that a big number of Christian churches had been built at that place. His merits is confirmed by a Chinese text of the 14th century explaining how a Sogdian named Mar-Sargis from Samarkand founded six Nestorian Christian churches there in improver to one in Hangzhou during the second half of the 13th century.[51] Nestorian Christianity had existed in China since the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD) when a Persian monk named Alopen came to the upper-case letter Chang'an in 653 to proselytize, as described in a dual Chinese and Syriac linguistic communication inscription from Chang'an (modern Xi'an) dated to the year 781.[52]

In 2012, the University of Tübingen sinologist and historian Hans Ulrich Vogel released a detailed analysis of Polo's description of currencies, salt production and revenues, and argued that the show supports his presence in People's republic of china because he included details which he could non have otherwise known.[53] [54] Vogel noted that no other Western, Arab, or Western farsi sources have given such accurate and unique details about the currencies of Cathay, for example, the shape and size of the paper, the utilise of seals, the various denominations of newspaper coin as well every bit variations in currency usage in unlike regions of Mainland china, such as the use of cowry shells in Yunnan, details supported by archaeological show and Chinese sources compiled long after Polo'due south had left Communist china.[55] His accounts of table salt production and revenues from the table salt monopoly are also accurate, and accord with Chinese documents of the Yuan era.[56] Economic historian Mark Elvin, in his preface to Vogel'south 2013 monograph, concludes that Vogel "demonstrates by specific example after specific example the ultimately overwhelming probability of the wide authenticity" of Polo'southward account. Many problems were acquired past the oral transmission of the original text and the proliferation of significantly different mitt-copied manuscripts. For instance, did Polo exert "political authorization" ( seignora ) in Yangzhou or simply "sojourn" ( sejourna ) there? Elvin concludes that "those who doubted, although mistaken, were not e'er being casual or foolish", but "the case as a whole had now been closed": the volume is, "in essence, authentic, and, when used with care, in broad terms to exist trusted equally a serious though plain not ever final, witness".[12]

Other travellers [edit]

City of Ayas visited by Marco Polo in 1271 , from Le Livre des Merveilles

Although Marco Polo was certainly the nigh famous, he was not the only nor the first European traveller to the Mongol Empire who afterward wrote an account of his experiences. Earlier thirteenth-century European travellers who journeyed to the court of the Dandy Khan were André de Longjumeau, William of Rubruck and Giovanni da Pian del Carpine with Benedykt Polak. None of them however reached China itself. Afterward travelers such as Odoric of Pordenone and Giovanni de' Marignolli reached China during the Yuan dynasty and wrote accounts of their travels.[48] [47]

The Moroccan merchant Ibn Battuta travelled through the Gilt Horde and Red china subsequently in the early-to-mid-14th century. The 14th-century writer John Mandeville wrote an business relationship of journeys in the East, but this was probably based on second-manus information and contains much apocryphal information.

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ ... volendosi ravvisare nella parola "Milione" la forma ridotta di un diminutivo arcaico "Emilione" che pare sia servito a meglio identificare il nostro Marco distinguendolo per tal modo da tutti i numerosi Marchi della sua famiglia. (Ranieri Allulli, MARCO POLO E IL LIBRO DELLE MERAVIGLIE - Dialogo in tre tempi del giornalista Qualunquelli Junior e dell'astrologo Barbaverde, Milano, Mondadori, 1954, p.26)

- ^ Polo 1958, p. xv.

- ^ Boulnois 2005.

- ^ Jackson 1998.

- ^ Library of Congress Field of study Headings, Book 2

- ^ a b Maria Bellonci, "Nota introduttiva", Il Milione di Marco Polo, Milano, Oscar Mondadori, 2003, p. XI [ITALIAN]

- ^ a b Repertorio informatizzato dell'antica letteratura franco-italiana

- ^ Fragment of Marco Polo's Il Milione in Franco-Venetian linguistic communication, Academy of Padua RIAlFrI Projection

- ^ ^ Marco Polo, Il Milione, Adelphi 2001, ISBN 88-459-1032-6, Prefazione di Bertolucci Pizzorusso Valeria, pp. x–xxi.

- ^ Taylor 2013, pp. 595–596.

- ^ Wood 1996.

- ^ a b Vogel 2013, p. nineteen.

- ^ Sofri (2001) "Il secondo fu che Marco east i suoi usassero, peel, per distinguersi da altri Polo veneziani, il nome di Emilione, che è l' origine prosaica del titolo che si è imposto: Il Milione."

- ^ Lindhal, McNamara, & Lindow, eds. (2000). Medieval Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Myths, Legends, Tales, Beliefs, and Customs – Vol. I. Santa Barbara. p. 368.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) ABC-CLIO - ^ The engagement usually given every bit 1292 was emended in a notation by Chih-chiu & Yung-chi (1945, p. 51), reporting that Polo's Chinese companions were recorded as preparing to exit in September 1290.

- ^ Sofri 2001.

- ^ a b Latham, Ronald "Introduction" pp. 7–20 from The Travels of Marco Polo, London: Folio Order, 1958 p. 11.

- ^ Maria Bellonci, "Nota introduttiva", Il Milione di Marco Polo, Milano, Oscar Mondadori, 2003, p. XI

- ^ Latham, Ronald "Introduction" pp. 7–xx from The Travels of Marco Polo, London: Folio Society, 1958 pp. xi–12.

- ^ Latham, Ronald "Introduction" pp. seven–20 from The Travels of Marco Polo, London: Folio Society, 1958 p. 12.

- ^ a b [Rinaldo Fulin, Archivio Veneto, 1924, p. 255]

- ^ a b UniVenews, 18.11.2019, "Un nuovo tassello della vita di Marco Polo: inedito ritrovato all'Archivio"

- ^ a b Natalis Alexandre, 1699, Apologia de'padri domenicani missionarii della Red china

- ^ Giovanni Michele, 1696 Galleria de'Sommi Pontefici, patriarchi, arcivescovi, e vescovi dell'ordine de'Predicatori, vol.2, p. 5

- ^ Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the West: 1221-1410 (New York: Routledge 2014), especially pp. 167-196. B. Roberg, "Dice Tartaren auf dem two. Konzil von Lyon 1274," Annuarium historiae conciliarum v (1973), 241-302.

- ^ Jean Richard, Histoire des Croisades (Paris: Fayard 1996), p.465

- ^ "1274: Promulgation of a Crusade, in liaison with the Mongols", Jean Richard, "Histoire des Croisades", p.502/French, p. 487/English

- ^ The exhibition in Venice jubilant the 7 hundredth anniversary of Polo'due south nativity L'Asia nella Cartographia dell'Occidente, Tullia Leporini Gasparace, curator, Venice 1955. (unverifiable)

- ^ The Accurate Letters of Columbus by William Eleroy Curtis. Chicago, United states: Field Columbian Museum. 1895. p. 115. Retrieved 8 May 2018 – via Internet Annal.

- ^ Marco Polo, Le Livre des merveilles p. 9

- ^ Kellogg 2001.

- ^ a b c d e Philippe Menard Marco Polo fifteen eleven 07 , retrieved 13 October 2021

- ^ Bibliothèque Nationale MS. français 1116. For details, see, A. C. Moule and Paul Pelliot, Marco Polo: The Description of the Earth (London, 1938), p.41.

- ^ Scansione Fr. 2810, in expositions.bnf.fr.

- ^ Polo, Marco (1350). "The Travels of Marco Polo – Earth Digital Library" (in Former French). Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ^ Iter Marci Pauli Veneti ex Italico Latine versum, von Franciscus Pippinus OP

- ^ Giovanni Michele, 1696 Galleria de'Sommi Pontefici, patriarchi, arcivescovi, east vescovi dell'ordine de'Predicatori, vol.2, p. 5

- ^ Its championship was Secondo book delle Navigationi et Viaggi nel quale si contengono 50'Historia delle cose de' Tartari, et diuversi fatti de loro Imperatori, descritta da 1000. Marco Polo, Gentilhuomo di Venezia.... Herriott (1937) reports the recovery of a 1795 copy of the Ghisi manuscript, clarifying many obscure passages in Ramusio'due south printed text.

- ^ "scritti gia piu di dugento anni (a mio giudico)."

- ^ "Rusticien" in the French manuscripts.

- ^ "The almost noble and famous travels of Marco Polo, together with the travels of Nicoláo de' Conti". annal.org. Translated by John Frampton (Second ed.). 1937.

- ^ Marco Polo, Le Livre des merveilles p. 173

- ^ Na Chang. "Marco Polo Was in China: New Evidence from Currencies, Salts and Revenues". Reviews in History.

- ^ Frances Forest, Did Marco Polo Go to Red china? (London: Secker & Warburg; Boulder, Colorado: Westview, 1995).

- ^ a b c Haw 2006, p. 1.

- ^ Haeger, John W. (1978). "Marco Polo in Mainland china? Problems with Internal Show". Bulletin of Sung and Yüan Studies. 14 (xiv): 22–30. JSTOR 23497510.

- ^ a b c d Haw 2006, pp. 52–57.

- ^ a b Ebrey, Patricia (2 September 2003). Women and the Family in Chinese History. Routledge. p. 196. ISBN9781134442935.

- ^ Haw 2006, pp. 53–56.

- ^ Haw 2006, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Emmerick 2003, p. 275.

- ^ Emmerick 2003, p. 274..

- ^ "Marco Polo was not a swindler – he actually did go to China". University of Tübingen. Alpha Galileo. sixteen April 2012. Archived from the original on 3 May 2012.

- ^ Vogel 2013.

- ^ "Marco Polo Did Become to China, New Research Shows (and the History of Paper)". The New Observer. 31 July 2013.

- ^ "Marco Polo was not a swindler: He really did go to Red china". Science Daily.

Farther reading [edit]

Delle meravigliose cose del mondo, 1496

Translations

- Polo, Marco; Rustichello da Pisa (1350). "Devisement du monde" (in Old French). World Digital Library, from the National Library of Sweden, M 304. Retrieved 27 Feb 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - — (1845). The Travels of Marco Polo. Translated by Hugh Murray. Harper & Brothers.

- — (1871), The Volume of Ser Marco Polo, the Venetian, vol. 1, 2, index, translated by Henry Yule, London: John Murray .

- — (1903), The Book of Ser Marco Polo, the Venetian, Concerning the Kingdoms and Marvels of the East, vol. 1, 2, index, translated by Henry Yule (3rd ed.), London: John Murray .

- — (1958). The Travels. Translated by Ronald Latham. London: Penguin Classics. ISBN978-0-14-044057-7.

- — (1968). Wright, Thomas (ed.). The Travels of Marco Polo The Venetian. Translated past William Marsden. AMS Press. OCLC 363429.

- — (2005). The Travels Of Marco Polo. Translated by Paul Smethurst. Barnes & Noble, Inc. ISBN0-7607-6589-8.

Full general studies

- Boulnois, Luce (2005). Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants . Hong Kong: Odyssey Books & Guides. pp. 311–335. ISBN962-217-721-2.

- Haw, Stephen Yard. (2006), Marco Polo's Communist china: A Venetian in the Realm of Khubilai Khan, Routledge Studies in the Early History of Asia, London; New York: Routledge, ISBN0415348501 .

- Larner, John (1999), Marco Polo and the Discovery of the World, New Haven: Yale Academy Press, ISBN0300079710 .

- Olschki, Leonardo (1960), Marco Polo's Asia: An Introduction to His "Description of the Globe" Called "Il Milione", translated past John A. Scott, Berkeley: University of California Press, OCLC 397577 .

- Taylor, Scott 50. (2013), "Merveilles du Monde: Marco Millioni, Mirabilia, and the Medieval Imagination, or the Bear on of Genre on European Curiositas", in Classen, Albrecht (ed.), Due east Meets Due west in the Heart Ages and Early on Modern Times: Transcultural Experiences in the Premodern World, Fundamentals of Medieval and Early Mod Civilization, vol. xiv, Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 595–610, doi:10.1515/9783110321517.595, ISBN9783110328783, ISSN 1864-3396 .

- Vogel, Hans Ulrich (2013), Marco Polo Was in China: New Evidence from Currencies, Salts and Revenues, Leiden; Boston: Brill, ISBN9789004231931 .

- Forest, Francis (1996). Did Marco Polo Go to China?. Bedrock: Westview Press. ISBN9780813389981.

Journal articles

- Chih-chiu, Yang; Yung-chi, Ho (September 1945). "Marco Polo Quits Cathay". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 9 (1): 51. doi:x.2307/2717993. JSTOR 2717993.

- Emmerick, R. E. (2003), "Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs", in Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.), The Cambridge History of Islamic republic of iran, Vol Three: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Cambridge University Printing, doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521200929.009 .

- Herriott, Homer (October 1937). "The 'Lost' Toledo Manuscript of Marco Polo". Speculum. 12 (i): 456–463. doi:ten.2307/2849300. JSTOR 2849300. S2CID 164177617.

- Jackson, Peter (1998). "Marco Polo and his 'Travels'" (PDF). Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 61 (ane): 82–101. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00015779.

Paper and spider web manufactures

- Kellogg, Patricia B. (2001). "Did yous Know?". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008.

- Sofri, Adriano (28 December 2001). "Finalmente Torna Il favoloso milione". La Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 27 Feb 2019.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Eatables has media related to Il milione. |

- Google map link with Polo's Travels Mapped out (follows the Yule version of the original work)

- The Travels of Marco Polo. (Yule-Cordier translation) Volume 1 at Project Gutenberg

- The Travels of Marco Polo. (Yule-Cordier translation) Volume 2 at Project Gutenberg

-

The Travels of Marco Polo public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Travels of Marco Polo public domain audiobook at LibriVox - The description of the world (Moule-Pelliot translation) at the Net Archive

- Interactive scholarly edition, with critical English language translation and multimodal resource mashup (publications, images, videos) Applied science Historical Memory.

doylesuchaked1974.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Travels_of_Marco_Polo

Post a Comment for "what did Marco Polo say in his writings that led some to disbelieve his stories"